How close is too close?

In this era of beauty influencers, filtered photographs, and an endless array of luxury cosmetic and skincare products marketed at high price points to achieve “the perfect look”, it is no wonder that the market for cheaper “copycat” cosmetic products is on the rise. In fact, selling products that are “inspired” by more expensive luxury brands is part of the core business model of many cheaper (imitator) brands.

However, any business seeking to imitate a successful product must be careful not to infringe the intellectual property rights of the luxury brand owner. Nevertheless, the current legal framework allows for some businesses to successfully toe the line, as can be seen in a number of recent cases. This article examines this legal framework, with some key take aways for leading brand and imitator business alike.

IP Tools Available to Brand Owners

Brand owners typically have the following tools available to them in order to protect their rights in this area:

- Registered Trade Marks (to protect brand names, logos and aspects of packaging);

- Designs (to protect the shape and visual appearance of the product, and packaging);

- Patents (to protect the specific formulation of the product, or functionality of devices such as applicators or functional packaging);

- Copyright (to protect imagery associated with the product); and

- Misleading and Deceptive Conduct under the Australian Consumer Law (to protect against consumer confusion arising in the context of the overall conduct of the imitator business).

Each of these rights have their benefits and limitations as explored below.

Trade Marks

A registered trade mark can be used to prevent another person from using a substantially identical or deceptively similar mark, as a badge of origin, in relation to the same or similar goods/services in relation to which the mark is registered.

An advantage of registered trade mark rights is that is not necessary to demonstrate that the consumer is likely to be misled or deceived in all the circumstances – the imitator may adopt certain strategies such as selling products at a different price point, through different outlets, and on packaging which includes other dissimilar devices, which in reality, reduces the prospect of confusion in the marketplace. Nevertheless if they adopt a trade mark that is similar to the brand owner’s registered rights in relation to the registered goods, this will in most circumstances be sufficient to establish trade mark infringement.

While this is a powerful right, “dupe” products often do not adopt similar brand names, but instead adopt other (non-registered) aspects of the overall brand get-up to signal to the consumer a connection between the products. In these circumstances, registered trade mark protection of the brand name is unlikely to offer a remedy for the brand owner.

Therefore, where a brand owner’s overall packaging may acquire a reputation in the marketplace, registration of not only the brand name, but the overall visual appearance of the packaging/product (such as labels, colour combinations or even the shape of packaging) should be considered. The capacity for such a registration to protect against an imitator will depend upon which aspects are copied by the imitator, and whether they are used as a “trade mark”.

Designs

Design registration protects the visual appearance of a product, such as its shape. This can be particularly useful for the protection of the unique packaging that is often a selling point of luxury cosmetic and skincare products. Design registration provides protection for up to 10 years.

In order to be valid, a design must be novel when compared with the prior art base. Not only must the design be unique when compared with others in the market, brand owners must also file a design application before their own product is launched, because the publication of the design by launching the product (anywhere in the world) will render ay future design application invalid (unless the grace period, explained below, applies).

Australian designs law has recently been amended to introduce a 12 month grace period (meaning that a design application can be filed up to 12 months after initial publication). Resulting design rights cannot be enforced against any imitator that adopted a similar design in the intervening period before the design application was actually filed but after the design may have already been on the market.

Many businesses in this area have a large array of products, and it can be expensive to file applications in relation to all products in the portfolio before knowing whether they will be commercially successful in the Australian market.

Nevertheless, for brand owners in this field, registered design rights can be amongst the most effective to enforce against imitators because the overall visual appearance of a product, including packaging and colours are a key feature of what imitator brands tend to copy in their cheaper alternatives. Brand owners should consider applying for design protection at the earliest opportunity, particularly where the packaging or appearance of a new product will be a unique and distinctive selling point.

Patents

Patents provide protection for the functionality of a product. They can, in this field, be used to protect novel formulations, devices (such as applicators) or unique packaging which has a functional effect. Patents can provide protection regardless of the get-up or branding adopted by an imitator product, but they are only granted for inventions that are considered new and inventive over the prior art.

Patents cannot be asserted against third parties until they are granted, and the patent application and grant process can take, in some cases, years. In a fast-moving consumer environment where “viral” products may only be on-trend for a couple of seasons, patent protection may not be achieved in time to enforce the rights against the imitator while they are still in the market. Successful luxury products are also not necessarily new compared with what was already available – they may simply be marketed more effectively than previous versions of the same product, in which case patent protection may not be available.

For truly new products and formulations, patents are a powerful tool that can provide protection against third party copycats regardless of the marketing strategy adopted by the imitator and are an important tool for innovators in this space.

Copyright

Copyright protects the reproduction of artistic works such as images and photographs, which may be used on the packaging of products. However, copyright does not protect the “idea” of an artistic work, only the specific expression of it. Therefore, imitator brands often use similar imagery that takes the “idea” of the artistic works, but expresses them in a different, non-infringing way. Currently, Australian baby snack food brand Little Bellies has commenced an action against supermarket Aldi for copyright infringement in relation to the similarities between the imagery on the respective packaging of their products. The outcome of this case will be instructive on the line between reproduction of a substantial part of an artwork and merely taking the “idea” behind the work in the context of imitator products.

Misleading and Deceptive Conduct/Passing Off

Misleading and deceptive conduct and passing off are often “catch-all” causes of action for any conduct by an imitator that is likely to lead to confusion in the market place. It is often relied upon in addition to or in the absence of any registered rights held by the brand owner.

Typically, the luxury brand owner alleges that the copying of certain aspects of the branding and get-up of the luxury product is likely to mislead or deceive customers into believing that there is a connection between the imitator and the luxury brand, or that the imitator’s products are in fact supplied or sponsored by the luxury brand.

In order to assess whether a consumer is likely to be misled, the overall circumstances are considered, including the price point of the respective products, the retail outlets in which they are sold, whether any similarities in the packaging are common to the field, and whether there are distinguishing features (such as a dissimilar product name) which make it clear to the customer that the imitator product is not supplied by or associated with the luxury brand.

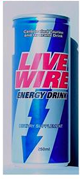

In some cases, imitator products (particularly those sold at similar outlets and at similar price points) are found to be misleading, as was the case in Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd [2002] FCAFC 157, where Sydneywide Distributors, by supplying an energy drink in a can that adopted the red, blue and silver colour scheme of the market leader Red Bull, was found to be engaging in misleading and deceptive conduct and passing off even though it was sold under the name “Livewire”.

vs

vs

In many cases, imitator products are often sold at a fraction of the price, in different retail outlets (e.g. supermarkets vs boutique high-end make-up stores), and in packaging that bears a completely dissimilar brand name to the original. In these cases, the consumer is under no illusion as to what they are purchasing – they know they are buying a copycat product in the hope that it is substitutable for the more expensive brand. In such instances, an action for misleading and deceptive conduct may not succeed, as can be seen in Moroccanoil Israel Ltd v Aldi Foods Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 823, where Aldi was found not to have engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct or passing off on account of supplying a range of hair care products containing Moroccan oil in packaging that used very similar blue labelling to the market leader Morrocanoil. However, Aldi was found to have engaged in other misleading representations in relation to the performance of the products, including that there was a representation that the amount of Moroccan oil in the product was sufficient to have an impact on its function, but in actual fact was included in too low a concentration to have an effect.

vs

vs

Misleading and deceptive conduct can be a useful tool for brand owners if the imitator’s conduct is causing confusion in the marketplace. It may be that the relevant misleading representation is not so much that the imitator product is the same as the luxury product or supplied by the luxury brand, but that the imitator product will do the same thing at a fraction of the cost, when in actual fact it does not exhibit the same quality or characteristics. The challenge in these cases will be supporting that proposition with evidence in a field where quality or effectiveness is often subjective. Brand owners should consider whether there are aspects of their products that can be objectively tested and compared with the imitator product to make good this argument, including the composition or inclusion of key ingredients (such as in the Moroccan Oil case).

Should you have any questions about whether your dupe is “too close” or are concerned about competitor imitations please do not hesitate to contact the author of this article on Bindhu.holavanahalli@wrays.com.au or on (08) 9216 5100.